RFK Jr. is right to say there’s an autism epidemic

Today the CDC announces autism rates have surpassed 3% of U.S. children, including 5% of boys. The health secretary may be wrong on vaccines, but the data support his insistence on a true increase.

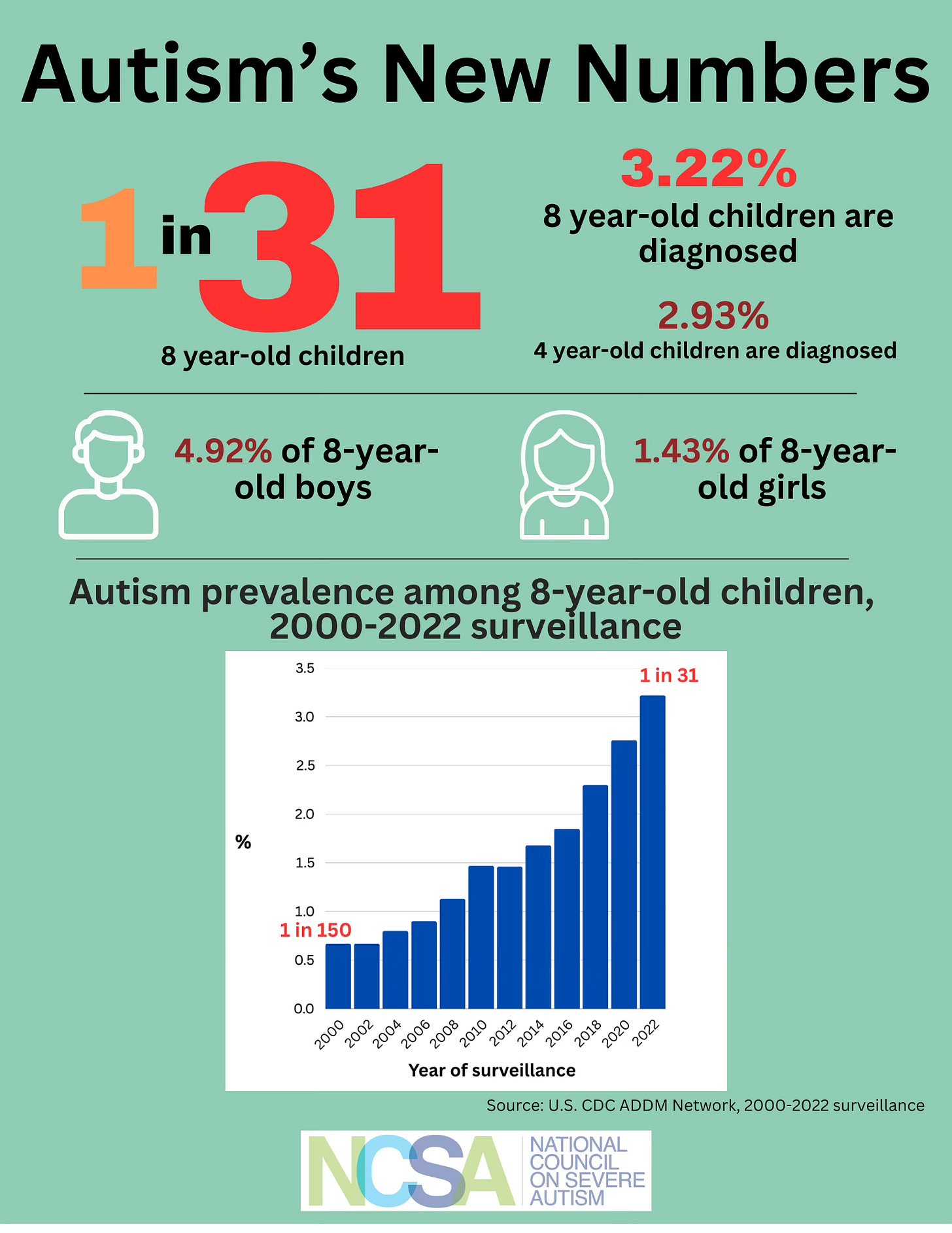

In President Trump’s televised April 10 cabinet meeting, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Secretary of Health and Human Services, dropped the news that the latest U.S. autism prevalence figure had reached 1 in 31 children, a preview of the official Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study published today.

The secretary even used that dread word, “epidemic.”

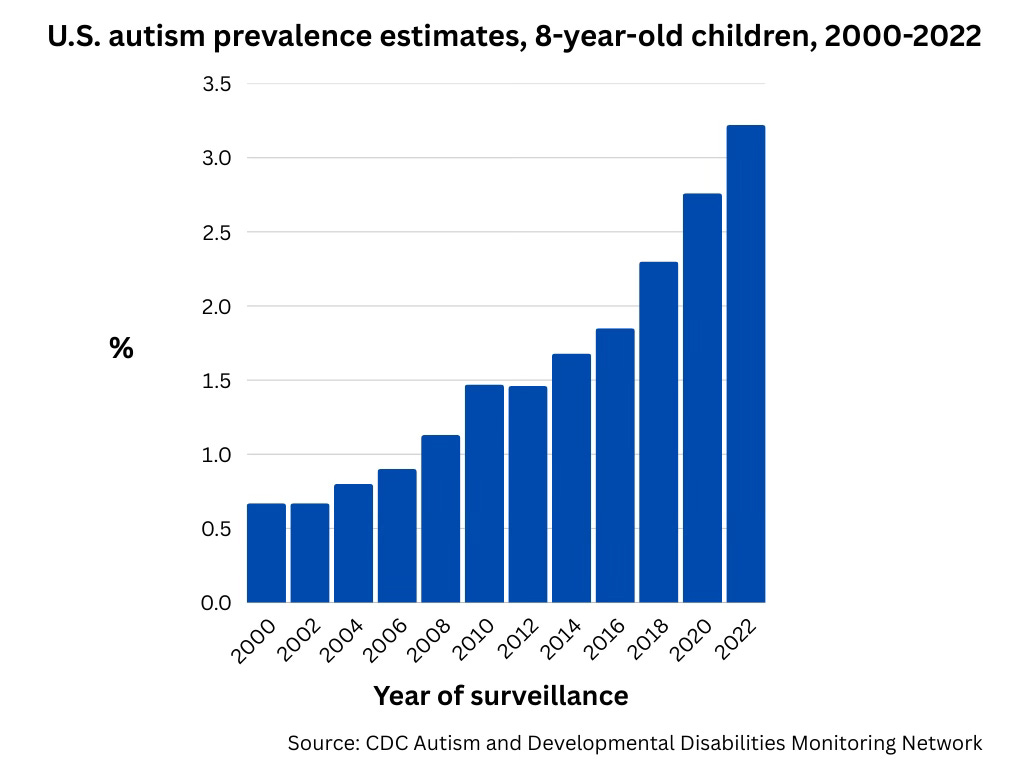

But does this new estimate — 3.22% of all eight-year-old children in 2022, up almost 500% from .67% in 2000 when the CDC first launched its autism surveillance program — warrant a gasp of epidemic shock, or just a ho-hum shrug? In other words, does the fact that we have for the first time passed 3% of eight-year-old children having autism truly reflect increasing rates of neurobehavioral disability in our children, or do these numbers merely mirror a trend toward better diagnosis?

Major media outlets have repeatedly supported the latter narrative with the refrain that the rising number of cases is mainly due to “growing awareness about the condition” and that “milder forms of autism and related conditions have been folded into the umbrella.”

Figure 1: Autism prevalence among 8 year-old children has steadily increased since the CDC began conducting surveillance in the year 2000. The new rate, 3.22% is up almost five-fold from the .67% rate first reported.

But a seasoned investigator in the CDC’s autism surveillance team disagrees with this “magical koan,” as he has called such rationalizations, invoked to wave away the increase.

“This is such a distortion“ says Walter Zahorodny, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at Rutgers University, who investigates autism prevalence, and has led the CDC’s efforts in New Jersey for more than two decades. “The media is so quick but also so shallow. They take no time to examine the data, and now the public is habituated to the message that the autism numbers don’t mean anything.”

Supporting RFK, Jr.’s talk of an autism epidemic, he stressed that the 4- and 8-year-old children counted by the CDC have serious neurobehavioral and learning impairments that for the most part would not have been missed before. Zahorodny says several lines of analysis that point to a true, and very dramatic, increase in autism rates over recent decades.

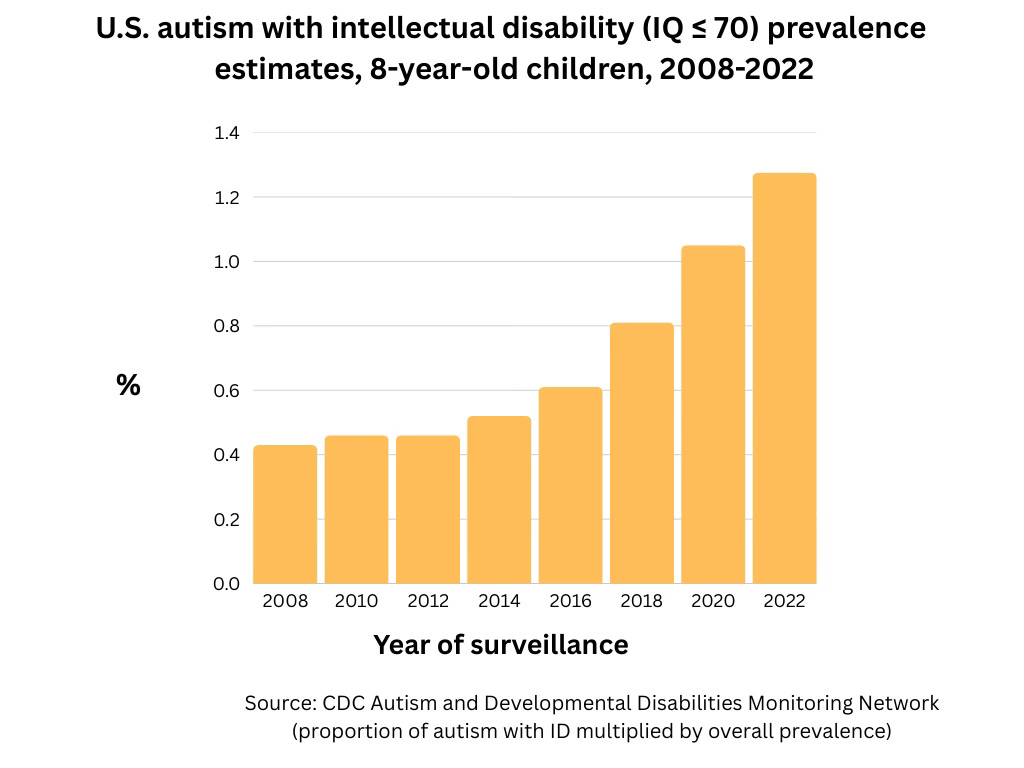

Isolating the CDC autism cases with co-occurring intellectual disability — as is the case with my two grown children with nonverbal profound autism, Jonathan and Sophie — you still see a sweeping increase over time. (Intellectual disability means an IQ of 70 or below.) This same upward trajectory applies to cases with IQs in the “borderline” range of 71-85.

Figure 2: Even when limited to cases of autism with intellectual disability, the autism prevalence rates have increased nearly 300%, from 0.43% in the 2008 cycle to 1.28% of eight year-old children in the 2022 cycle.

The portion of autism cases with intellectual disability has been climbing in recent years, contrary to the common assertion that the system is just growing in mild cases. In this latest cycle about 40% of the autistic 8-year-olds were classified as having intellectual disability, up from 35% four years ago.

“Every subtype of autism has increased,” said Zahorodny. “If you think it’s just mild cases, that’s just not the case.” He also took issue with the word “mild.” “Even the children without intellectual impairment can be severely impaired. They have much more complicated behavioral and psychiatric co-morbidities, especially anxiety disorder but also mood disorder, ADHD, sleep problems, and self-injurious behaviors.”

“If you think it’s just mild cases, that’s just not the case.”

He also said the trope of “broadened ascertainment” is generally false in the CDC network. In the study cycles between 2000 and 2016 the researchers used an exhaustive, expensive and time-intensive “active case finding” method, which identified not just diagnosed cases but also children without a formal diagnosis. In New Jersey and elsewhere, he said “it yielded approximately 20-25% additional cases.”

But for the 2018 ascertainment cycle through the 2022 cycle announced today, in order to save on time and expense the CDC switched to relying solely on pre-existing diagnoses, whether through medical or school systems. Zahorodny had predicted that autism rates would fall because of the more restrictive methods. But that didn’t happen. Rates kept climbing, particularly among non-white children.

He also criticized the commonly invoked idea that the switch from DSM-4 (referring to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual used by psychiatrists to diagnose mental disorders) to DSM-5 criteria in 2013 open the floodgates to milder cases in the CDC system. He said that as applied in the CDC cycles, “the DSM-5 criteria are more restrictive in DSM-5 than DSM-4” and that a CDC study found no significant differences in ascertainment between the two diagnostic schemes.

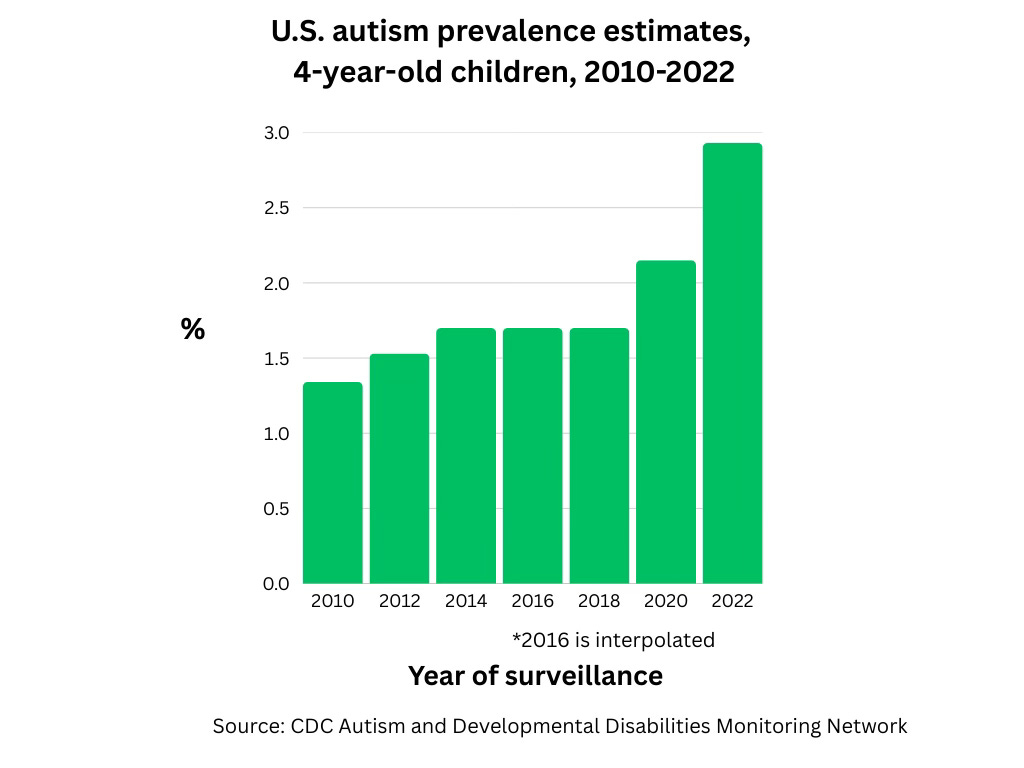

Zahorodny also pointed out the steady increase in very young children, that is 4-year olds tracked by the CDC program, reaching 2.93% for 2022 compared to 1.34% in 2010 when the agency began tracking these preschoolers in some states to help gauge trends in autism prevalence. “I always expected that the 4-year rate would lag the 8-year rate” owing to the challenges of obtaining an early diagnosis and the fact that children with greater impairments tend to be identified early.

“But on the contrary, we are now seeing five states, including California and New Jersey that have a 4-year-old rate that’s higher than the 8-year-old rate, a signal that childhood autism prevalence will continue to trend upward. This is like a guarantee that the trend is not plateauing, it’s increasing,” he said.

Figure 3: Autism prevalence is up sharply in 4-year-olds, from 1.34 in the 2010 cycle, when the CDC began tracking 4-year-olds, to more than doubling to 2.93% in 2022.

Zahorodny said the persistence of the skewed sex ratio contradicts the idea that rates are climbing just because we are capturing more girls. In this latest cycle, nearly 5% (4.92%) of all 8-year-old boys were identified as having autism, compared to 1.43% among girls. “I’m certain the prevalence is higher among males compared to females,” he said, whether the ratio is closer to 3 to 1 or 4 to 1. “I don’t think it’s ever going to be the case we will find a hidden group of girls who were never appreciated.” Even the new CDC report cautions against this interpretation, explaining that the difference in prevalence between boys and girls widened between 2020 and 2022.

“I don’t think it’s ever going to be the case we will find a hidden group of girls who were never appreciated.”

Finally, Zahorodny commented on the notable demographic shift in recent CDC cycles. “A pattern of higher SES (socioeconomic status) having higher autism prevalence persisted for over 10 years. This association of wealth and autism prevalence is very unusual, in most cases of health and disease we see the lower SES has higher morbidity. But recently there’s a shift. The white rate is a little higher but minority rates have exploded, even beyond the rates in whites. It’s not just that we are getting better at identifying under-served children,” he said.

The word “epidemic” is appropriate to describe the ascension of autism since the 1990s, says Alexander MacInnis, MS, an independent epidemiological researcher who has published on California autism data, and who has a daughter with profound autism. “Epidemic has a definition, and not just for infectious disease,” he said. “It can be a disorder where more cases are occurring than what you would expect based on history. We have massively increased birth cohort prevalence from every data source I can find showing very consistent increases, even within studies, which removes bias.”

“Overall we see about a 7% increase in autism cases per birth year,” he said. “Does this meet the definition of an epidemic? It does.” MacInnis also noted that autism cases in California’s developmental disability system, which serves only significantly disabling forms of autism, have exploded from about 4,000 in 1989 to about 206,000 today.

Zahorodny agrees, saying that “ASD is a serious neurodevelopmental disorder which has increased without interruption across all communities and subgroups.” And he says we should brace ourselves for numbers to go up: “The 3.22% number is, if anything, likely an underestimate.” Citing emerging data from New Jersey and other sources he says that soon autism’s “new normal will be 5%.”

Citing emerging data from New Jersey and other sources Zahorodny says that soon autism’s “new normal will be 5%.”

Kennedy claimed that he will be able to determine the cause of autism by September, a claim that researchers I spoke with found somewhere between highly unlikely and preposterous. While Zahorodny appreciates the Secretary’s urgency, he pleads for a more scientifically sound path. "We don't understand the drivers or risk factors for this increase, but we should not waste time and money” on unproven hypotheses like vaccines, which has long been a priority for Kennedy.

Marc Weisskopf, professor of environmental epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said “The elephant in the room is there are also environmental contributors that are causing these changes, we need to be looking across many fronts,” but cautioned that “money used in the direction of vaccines could be better spent. We want to figure this out as fast as we can.” He also feared any re-direction of NIH funds away from more plausible research questions.

“The elephant in the room is there are also environmental contributors that are causing these changes.”

Antonio Hardan, MD, director of the autism program at Stanford Medical Center, expressed concern about the on-the-ground implications for families and individuals challenged by autism. While he would rather see rigorous in-person gold-standard evaluations for a small representative percentage of participants to vet the diagnoses in the CDC study, he said that even the children who might not meet strict criteria “are individuals who are struggling at home, school, socially and in the community, and need more clinical attention.” He wants to see the growing prevalence translate into greater efforts to provide programs and clinical care to support autistic children across their lifespan.

“This number [1 in 31] is crying for help,” he said.

Jill Escher is president of the National Council on Severe Autism and founder of the Escher Fund for Autism. More at jillescher.com.

I have worked with children with autism for 36 years. I have a grandson with autism. So I know what real autism looks like. And there has definitely been a sharp increase in the last 10 years or so. Yes, some of it is the larger parameters we use to diagnose autism (many who I think are misdiagnosed), but there has DEFINITELY been an increase in the numbers of children with more severe autism as well. Ask any prek- through grade 5 teacher. Ask any school district that is having to create more self-contained autism programs. It is real. I am not talking about the kid who used to be considered a nerd who gets good grades and who has an obsession with Pokémon who we now call autistic. I am talking about kids who are non or minimally verbal, who need ABA and AAC devices, very specialized instruction,and one:one para support. It’s a topic of conversation we often have in our sped meetings.

I tried to talk about as many theories about autism as possible in this (very long) essay and to examine evidence for them … definitely missed some factors though.

I didn’t highlight this in the essay, but a lot of the proposed environmental toxins and nutritional factors were introduced or became widespread at two key points — the late 70s or early 80s, and the late 90s.

https://thecassandracomplex.substack.com/p/what-causes-autism